LOUISVILLE, Tenn. — When a big storm hits, Peninsula Hospital could be underwater.

At this decades-old psychiatric hospital on the edge of the Tennessee River, an intense storm could submerge the building in 11 feet of water, cutting off all roads around the facility, according to a sophisticated computer simulation of flood risk.

Aurora, a young woman who was committed to Peninsula as a teenager, said the hospital sits so close to the river that it felt like a moat keeping her and dozens of other patients inside. KFF Health News agreed not to publish her full name because she shared private medical history.

“My first feeling is doom,” Aurora said as she watched the simulation of the river rising around the hospital. “These are probably some of the most vulnerable people.”

Covenant Health, which runs Peninsula Hospital, said in a statement it has a “proactive and thorough approach to emergency planning” but declined to provide details or answer questions.

Peninsula is one of about 170 American hospitals, totaling nearly 30,000 patient beds from coast to coast, that face the greatest risk of significant or dangerous flooding, according to a months-long KFF Health News investigation based on data provided by Fathom, a company considered a leader in flood simulation. At many of these hospitals, flooding from heavy storms has the potential to jeopardize patient care, block access to emergency rooms, and force evacuations. Sometimes there is no other hospital nearby.

Much of this risk to hospitals is not captured by flood maps issued by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which have served as the nation’s de facto tool for flood estimation for half a century, despite being incomplete and sometimes decades out of date. As FEMA’s maps have become divorced from the reality of a changing climate, private companies like Fathom have filled the gap with simulations of future floods. But many of their predictions are behind a paywall, leaving the public mostly reliant on free, significantly limited government maps.

“This is highly concerning,” said Caleb Dresser, who studies climate change and is both an emergency room doctor and a Harvard University assistant professor. “If you don’t have the information to know you’re at risk, then how can you triage that problem?”

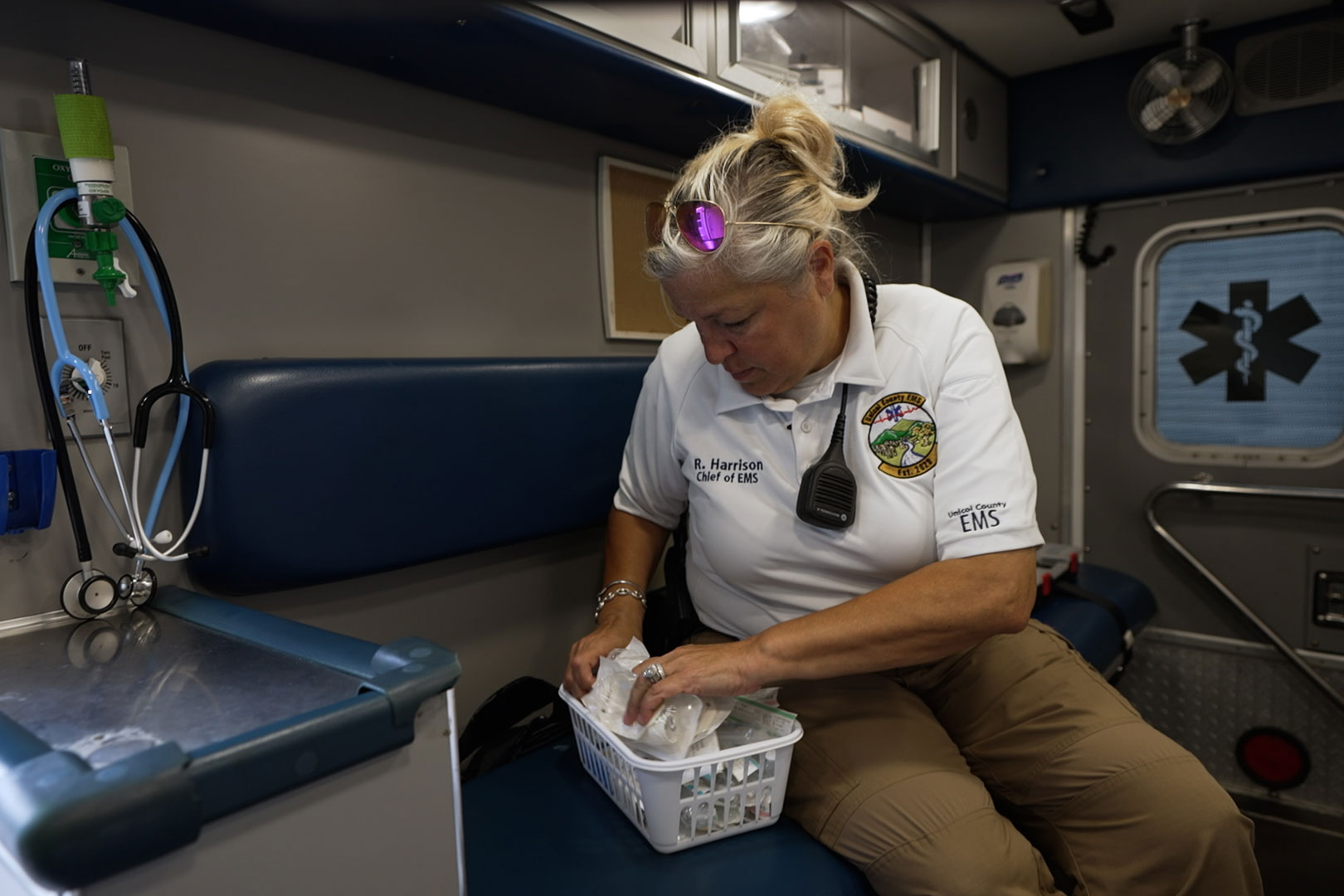

The deadliest hospital flooding in modern American history occurred 20 years ago during Hurricane Katrina, when the bodies of 45 people were recovered from New Orleans’ Memorial Medical Center, including some patients whom investigators suspected were euthanized. More flooding deaths were narrowly avoided one year ago when helicopters rescued dozens of people as Hurricane Helene engulfed Unicoi County Hospital in Erwin, Tennessee.

Rebecca Harrison, a paramedic, called her children from the Unicoi roof to say goodbye.

“I was scared to death, thinking, ‘This is it,’” Harrison told CBS News, which interviewed Unicoi survivors as part of KFF Health News’ investigation. “Alarms were going off. People were screaming. It was chaos.”

The investigation — among the first to analyze nationwide hospital flood risk in an era of warming climate and worsening storms — comes as the administration of President Donald Trump has slashed federal agencies that forecast and respond to extreme weather and also dismantled FEMA programs designed to protect hospitals and other important buildings from floods.

When asked to comment, FEMA said flooding is a common, costly, and “under appreciated” disaster but made no statement specific to hospitals. Spokesperson Daniel Llargués defended the administration’s changes to FEMA by reissuing an August statement that dismissed criticism as coming from “bureaucrats who presided over decades of inefficiency.”

Alice Hill, an Obama administration climate risk expert, said the Trump administration’s dismissal of climate change and worsening floods would waste billions of dollars and endanger lives.

In 2015, Hill led the creation of the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard, which required that hospitals and other essential structures be elevated or incorporate extra flood protections to qualify for federal funding.

FEMA stopped enforcing the standard in March.

“People will die as a result of some of the choices being made today,” Hill said. “We will be less prepared than we are now. And we already were, in my estimation, poorly prepared.”

‘Flood Risk Is Everywhere’

The KFF Health News investigation identified more than 170 hospitals facing a flood risk by comparing the locations of more than 7,000 facilities to peer-reviewed flood hazard mapping provided by Fathom, a United Kingdom company that simulates flooding in spaces as small as 10 meters using laser-precision elevation measurements from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Hospitals were determined to have a significant risk if Fathom’s 100-year flood data predicted that a foot or more of water could reach a considerable portion of their buildings, excluding parking garages, or cut off road access to the hospital. A 100-year flood is an intense weather event that has roughly a 1% chance of occurring in any given year but can happen more often.

The investigation found heightened flood risks at large trauma centers, small rural hospitals, children’s hospitals, and long-term care facilities that serve older and disabled patients. At least 21 are critical access hospitals, with the next-closest hospital 25 miles away, on average.

Flooding threatens dozens of hospitals in coastal areas, including in Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and New York. Farther inland, flooding of rivers or creeks could envelop other hospitals, particularly in Appalachia and the Midwest. Even in the sun-soaked cities and arid expanses of the American West, storms have the potential to surround some hospitals with several feet of pooling water, according to Fathom’s data.

These findings are likely an undercount of hospitals at risk because the investigation overlooked pockets of potential flooding at some hospitals. It excluded facilities like stand-alone ERs, outpatient clinics, and nursing homes.

“The reality is that flood risk is everywhere. It is the most pervasive of perils,” said Oliver Wing, the chief scientific officer at Fathom, who reviewed the findings. “Just because you’ve never experienced an extreme doesn’t mean you never will.”

Dresser, the ER doctor, said even a small amount of flooding can shut down an unprepared hospital, often by interrupting its power supply, which is needed for life-sustaining equipment like ventilators and heart monitors. He said the most vulnerable hospitals would likely be in rural areas.

“A lot of rural hospitals are now closing their pediatric units, closing their psychiatry units,” Dresser said. “In a financially stressed situation, it can be hard to prioritize long-term threats, even if they are, for some institutions, potentially existential.”

Urban hospitals can face dangerous flooding, too. Fathom’s data predicts 5 to 15 feet of water around neighboring hospitals — Kadlec Regional Medical Center and Lourdes Behavioral Health — that straddle a tiny creek in Richland, Washington.

By Fathom’s estimate, a 100-year flood could cause the nearby Columbia River to spill over a levee that protects Richland, then loosely follow the creek to the hospitals. Some of the deepest flooding is estimated around Lourdes, which was built on land the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers set aside in 1961 as a “ponding and drainage easement.”

At the time, this land was supposed to be capable of storing enough water to fill at least 40 Olympic-size swimming pools, according to military documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. A mental health facility has occupied this spot since the 1970s.

Both Kadlec and Lourdes said in statements that they have disaster plans but did not answer questions about flooding. Tina Baumgardner, a Lourdes spokesperson, said government flood maps show the hospital is not in a 100-year flood plain.

This is not uncommon. Of the more than 170 hospitals with significant flood risk identified by KFF Health News, one-third are located in areas that FEMA has not designated as flood hazard zones.

Sometimes the difference is stark. For example, at Ochsner Choctaw General in Alabama — the only hospital for 30 miles in any direction — FEMA maps suggest a 100-year flood would overflow a nearby creek but spare the hospital. Fathom’s data predicts the same event would flood most of the hospital with 1 to 2 feet of water, including the ER and the helicopter pad.

Ochsner Health did not answer questions about flooding preparations at Choctaw General.

FEMA flood maps were launched in the ’60s as part of the National Flood Insurance Program to determine where insurance is required and building codes should include flood-proofing. According to a FEMA statement, the maps show only a “snapshot in time” and are not intended to predict where flooding will or won’t happen.

FEMA spokesperson Geoff Harbaugh said the agency intends to modernize its maps through the Future of Flood Risk Data initiative, which will enable the agency to “better project flood risk” and give Americans “the information they need to protect their lives and property.”

The program was launched by the first Trump administration in 2019 but has since received sparse public updates. Harbaugh declined to provide a detailed update or timeline for the program.

Chad Berginnis, executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, said it is unknown whether FEMA is still trying to upgrade its maps under Trump, as the agency has cut off communications with outside flooding experts.

“There has been not a single bit of loosening of what I’m calling the FEMA cone of silence,” Berginnis said. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Floods are expected to worsen as a warming climate fuels stronger storms, drenching areas that are already flood-prone and bringing a new level of flooding to areas once considered lower risk.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has said that 2024 was the warmest year on record — more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit higher than the 20th-century average. Scientists across the globe have estimated that each degree of global warming correlates to a 4% increase in the intensity of extreme rainfall.

“Warmer air can hold more moisture, so this leads us to experience heavier downpours,” said Kelly Van Baalen, a sea level rise expert at the nonprofit Climate Central. “A 100-year flood today could be a 10-year flood tomorrow.”

Intensifying storms raise concerns about Peninsula Hospital, which has operated for decades mere feet from the Tennessee River but has no known history of flooding.

Peninsula spokesperson Josh Cox said the river is overseen by the Tennessee Valley Authority, which uses dams to manage water levels and generate electricity. Estimates provided by the TVA suggest the dams could keep Peninsula dry even in a 500-year flood.

Fathom, however, said its flood simulation accounts for the dams and stressed that a large enough storm could drop more rain than even the TVA could control. These predictions are echoed by another flood modeling firm, First Street, which also says an intense storm could cause more than 10 feet of flooding in the area around Peninsula.

“It’s a hospital right on the banks of a major American river,” said Wing, the Fathom scientist. “It just isn’t conceivable that such a location is risk-free.”

Jack Goodwin, 75, a retired TVA employee who has lived next to Peninsula for three decades, said he was confident the dams could protect the area. But after reviewing Fathom’s predictions, Goodwin began to research flood insurance.

“Water can rise quickly and suddenly, and the destruction is tremendous,” he said. “Just because we’ve never seen it here doesn’t mean we won’t see it.”

‘All the Elements of a Real Disaster’

One year ago, as Hurricane Helene carved a deadly path across Southern Appalachia, Angel Mitchell was visiting her ailing mother at Unicoi County Hospital in the tiny town of Erwin, Tennessee.

Swollen by Helene, the nearby Nolichucky River spilled over its banks and around the hospital, which was built in a flood plain. Staff tried to bar the doors, Mitchell said, but the water got in, trapping her and others inside. The lights went out. People fled to the roof, where the roar of rushing water nearly drowned out the approach of rescue helicopters, Mitchell said.

Ultimately, 70 people from the hospital, including Mitchell and her mother, were airlifted to safety on Sept. 27, 2024. The hospital remains closed, and the company that owns it, Ballad Health, has said its reopening is uncertain.

“Why allow something — especially a hospital — to be built in an area like that?” Mitchell told CBS News. “People have to rely on these areas to get medical help, and they’re dangerous.”

Beyond Unicoi, KFF Health News identified 39 inland hospitals — including 16 in Appalachia — that Fathom predicts could flood when nearby rivers, creeks, or drainage canals overspill their banks, even in storms far less intense than Helene.

For example, in the Cumberland Mountains of southwestern Virginia, a 100-year flood is projected to cause Slate Creek to engulf Buchanan General Hospital in more than 5 feet of water.

Near the Great Lakes in Erie, Pennsylvania, LECOM Medical Center and Behavioral Health Pavilion could become flooded by a small drainage creek that is less than 50 feet from the front door of the ER.

Neither Buchanan nor LECOM responded to questions about flooding or preparations.

And in West Virginia’s capital of Charleston, where about 50,000 people live at the junction of two rivers in a wide and flat valley, a single storm could potentially flood five of the city’s six hospitals at once, along with schools, churches, fire departments, and other facilities.

“I hate to say it,” said Behrang Bidadian, a flood plain manager at the West Virginia GIS Technical Center, “but it has all the elements of a real disaster.”

At the largest hospital in Charleston, CAMC Memorial Hospital, Fathom predicts that the Kanawha River could bring as much as 5 feet of flooding to the ER. Across town, the Elk River could surround CAMC Women and Children’s Hospital, cutting off all exits.

And in the center of the city, where the overflowing rivers are predicted to merge, Thomas Orthopedic Hospital could be besieged by more than 10 feet of water on three sides.

WVU Medicine, which owns Thomas Orthopedic Hospital, did not respond to requests for comment.

CAMC spokesperson Dale Witte said the hospital system is aware of its flood risk and has prepared by elevating electrical infrastructure and acquiring flood-proofing equipment, like a deployable floodwall. CAMC also regularly revises and drills its disaster plans, Witte said, although he added that hospitals there have never been tested by a real flood.

Shanen Wright, 48, a lifelong Charleston resident who lives near CAMC Memorial, said many in the city have little worry about flooding in the face of more immediate problems, like the opioid epidemic and the decline of manufacturing and mining.

Tugboats and coal barges sail past his neighborhood as if they were cars on his street.

“It’s not to say it’s not a possibility,” he said. “I’m sure the people in Asheville and the people in Texas, where the floods took so many lives, they probably didn’t see it coming either.”

‘The Water Is Coming’

Despite wide scientific consensus that climate change fuels more dangerous weather, the Trump administration has taken the position that concerns about global warming are overblown. In a speech to the United Nations in September, Trump called climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world.”

The Trump administration has made deep staff and funding cuts to FEMA, NOAA, and the National Weather Service. At FEMA, the cuts prompted 191 current and former employees to publish a letter in August warning that the agency is being dismantled from within.

Daniel Swain, a University of California climate scientist, said the administration’s rejection of climate change has left the nation less prepared for extreme weather, now and in the future.

“It’s akin to enforcing malpractice scientifically,” Swain said. “Imagine making a medical decision where you are not allowed to look at 20% of the patient’s vital signs or test results.”

Under Trump, FEMA has also taken actions critics say will leave the nation more vulnerable to flooding, specifically:

- FEMA disbanded the Technical Mapping Advisory Council, which had repeatedly pushed the agency to modernize its flood maps to estimate future risk and account for the impacts of climate change.

- FEMA canceled its Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program, which provided grants to help communities and vital buildings, including hospitals, protect themselves from floods and other natural disasters.

- And after stopping enforcement early this year, FEMA intends to rescind the Federal Flood Risk Management Standard, which was designed to harden buildings against future floods and save tax dollars in the long run.

Berginnis, of the Association of State Floodplain Managers, said the administration’s unwillingness to prepare for climate change and worsening storms would result in a dangerous and costly cycle of flooding, rebuilding, and flooding again.

“The president is saying we are closed for business when it comes to hazard mitigation,” Berginnis said. “It bugs me to no end that we have to have reminders — like people dying — to show us why it’s important to make these investments.”

FEMA did not answer specific questions about these decisions. In the statement to KFF Health News, spokesperson Llargués touted the administration’s response to flooding in Texas and New Mexico and said FEMA had provided billions of dollars to help people and communities recover and rebuild. He did not mention any FEMA funding for protecting against future floods.

Few hospitals understand this threat more than the former Coney Island Hospital in New York City, which has suffered catastrophic flooding before and has prepared for it to come again.

Superstorm Sandy in 2012 forced the hospital to evacuate hundreds of patients. When the water receded, fish and a sea turtle were found in the building.

Eleven years later, the facility reopened as Ruth Bader Ginsburg Hospital, transformed by a FEMA-funded $923 million reconstruction project that added a 4-foot floodwall and elevated patient care areas and utility infrastructure above the first floor.

It is now likely one of the most flood-proofed hospitals in the nation.

But, so far, no storm has tested the facility.

Svetlana Lipyanskaya, CEO of NYC Health+Hospitals/South Brooklyn Health, which includes the rebuilt hospital, said the question of flooding is “not an if but a when.”

“I hope it doesn’t happen in my lifetime,” she said, “but frankly, I’d be surprised. The water is coming.”

After Hurricane Helene made landfall a year ago, a raging river flooded a rural hospital in eastern Tennessee. Patients and employees were rescued from the rooftop. Floods have hit hospitals from New York to Nebraska to Texas in recent years. We wanted to determine how many other U.S. hospitals face similar peril. Ultimately, we found more than 170 hospitals at risk.

For this analysis, we used data from Fathom, a United Kingdom-based company that specializes in flood-risk modeling across the globe. To assess the United States’ vulnerability, Fathom uses sophisticated computer simulations and detailed terrain data covering the country. It accounts for environmental factors such as climate change, soil conditions, and many rivers and creeks not mapped by other sources. Fathom’s modeling has been peer-reviewed and used by insurance companies, the World Bank, the Nature Conservancy, and government agencies in Florida, Texas, and elsewhere. The Iowa Flood Center has validated Fathom’s U.S. data.

Through a data use agreement, Fathom shared its U.S. mapping data that predicts areas with at least a 1% chance of flooding in any given year. Fathom’s data estimates the effects of three main types of flooding: coastal, fluvial (from overflowing rivers, lakes, or streams), and pluvial (rainfall that the ground can’t absorb). The data also accounts for dams, reservoirs, and other structures that defend against floods.

To identify at-risk hospitals, we used a publicly available Department of Homeland Security database containing the GPS coordinates of more than 7,000 short-term acute, critical access, rehab, and psychiatric hospitals — basically any hospital with inpatient services. (DHS under the Trump administration has discontinued public access to the database, so data for hospitals and other infrastructure is no longer widely available.)

Using GPS coordinates as the centerpoint, we created a circle with a 150-yard radius around each hospital, which in most cases captured the building plus nearby grounds and access roads. We then mapped Fathom’s flood-risk data to see where it overlapped with these circles. We started by looking for hospitals where at least 20% of the circle’s area had a predicted flood depth of at least 1 foot. That gave us an initial list of more than 320 hospitals across the U.S.

From there, we visually inspected those hospitals using mapping software and Google Maps, both satellite and street view. We trimmed our list to only the hospitals where a considerable portion of the building or all access roads were predicted to have at least a foot of flooding.

If two hospitals were mapped to the same building — for instance, a small rehab facility within a large hospital — we counted only one hospital. We also excluded hospitals recently converted to nursing homes or for other uses.

We ended up with a list of 171 hospitals across the U.S. That is most likely an undercount. Some hospitals could still face significant impact from flooding that is not deep enough or widespread enough to fit our methodology. Our analysis also does not account for how flooding farther from a hospital could affect employees or patients. And it does not assess what steps hospitals may have already taken to prepare for severe weather events.

We also ran a spatial analysis comparing Fathom’s data with flood hazard maps from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which in many cases are incomplete or haven’t been updated in years. We found that about a third of hospitals identified as flood risks by Fathom’s data did not overlap at all with FEMA’s 100- or 500-year hazard areas.

Fathom provided guidance and feedback as we developed our analysis.

CBS News correspondent David Schechter and photojournalist Chance Horner contributed to this report.

#Hospitals #Face #Major #Flood #Risk #Experts #Trump #Making #Worse

At Least 170 US Hospitals Face Major Flood Risk. Experts Say Trump Is Making It Worse.